Dr Somah's Speech at the Private Sector Investment Symposium

Written by Syrulwa Somah, PhD |

Friday, 05 October 2007 |

...In essence, prioritizing education, health, and infrastructure development” is the best way forward for Liberia in its national reconstruction and economic stabilization drives. For I believe that while the lack of job and housing opportunities may seem on the surface as the most pressing demands in Liberia today, the reality is that without health and education, the chances of many Liberians occupying new homes and taking over new jobs in the near future are slim. I believe that if in this age of information technology and economic globalization the Liberian educational system is not revamped to train Liberians in the relevant marketable skills that will enable Liberians to compete amongst themselves in Liberia and with people on the international market, then the country will be doomed to failure....

-------------------------------------------

Health & Education Imperatives for the New Liberia: A Proposal for Collective Action A Presentation

By

Syrulwa Somah, PhD

Executive Director, Liberian History, Education and Development, Inc. (LIHEDE) Greensboro, NC

&

Associate Professor, Environmental Health and Occupational Safety & Health

NC A&T State University, Greensboro, NC

delivered at

The “Private Sector Investment Symposium on the Goal of Rebuilding the Liberian Nation.”

Washington, DC, USA

October 1, 2007

His Excellency Ambassador Charles Minor and members of the Liberian Embassy;

Distinguished dignitaries and platform guests;

Fellow Liberians and friends of Liberia;

Ladies and Gentlemen:

I am honored by the invitation of organizers of this great forum for me to share with you my thoughts on the roles of health and education in the reconstruction of Liberia. Most of my remarks at this forum will center on two major themes. The first theme will focus on education, and it will deal mostly with the need to restructure the educational system in Liberia to develop the manpower needs of Liberia within the context of Liberian values, culture, and development goals and aspirations. The second theme will focus on health, and it will stress the need for collaborative efforts between the Liberian government and non-governmental organizations to build upon current national efforts aimed at controlling, preventing, and eradicating malaria in Liberia, the number one killer disease in Liberia today. Under the health theme, I will also call for concrete efforts among governmental and nongovernmental organizations in Liberia to accelerate the fight against malaria and all other preventable diseases in Liberia that continued to take money away from the national development budget.

However, before I touch on these two themes, please permit me to register how gratified I am about the opportunity extended to me and my organization, the Liberian History, Education, and Development, Inc. (LIHEDE), to address this all-important “Private Sector Investment Symposium on the Goal of Rebuilding the Liberian Nation.” I think it is an open secret that the fourteen-year civil war in Liberia from 1989 to 2003 greatly hindered the development goals and aspirations of the Liberian nation and people in very serious ways. And today, Liberia, Africa’s oldest black republic, is desperately in need of housing, transportation, employment, health, education, and other opportunities to recover from the negative effects of the civil war. Moreover, the gravity and urgency with which Liberians of all walks of life are making demands on the Unity Party government of President Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf for ready-made solutions to their poor socioeconomic conditions have become too overwhelming for the government, to say the lest. Hence, one thing that all Liberians and friends of Liberia can do in the interim process of rebuilding Liberia is to come together as we have done at this forum, to discuss strategies and plans for the likely next best steps that Liberia must take to ease the present predicament of the Liberian nation and people. And I submit that two of the most pressing planning tools for any reconstruction efforts in Liberia right now are education and health.

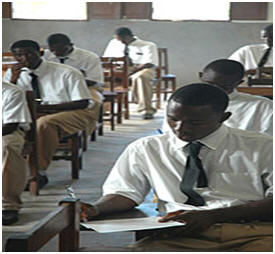

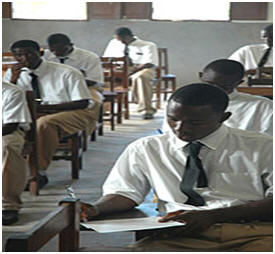

In this specific case, I want to draw attention to the economic and educational successes of the Asian nations of Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan, which faced similar problems in the past as Liberia today, but took steps to improve the living standard of their people. In the 1960s, Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan, now dubbed the “Four Asian Tigers,” were relatively poor nations with abundance of cheap labor just like Liberia today, but by reforming their educational systems, these nations were able to leverage this combination of educational reform and cheap labor into a creating productive workforce that continued to stimulate socioeconomic growth and development. Thus, on the economic front, the “Asian Tigers” pursued an export-driven model of economic development that basically focused on developing goods for export to highly-industrialized nations by discouraging. Domestic consumption through government policies such as high tariffs. And on the education front, the Four Asian Tigers singled out education as a means of improving productivity by focusing on the improvement of the education system at all levels. Heavy emphasis was placed on ensuring that all children in those countries acquiring elementary education and compulsory high school education, while money was also spent on improving the local college and university systems. Today, Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan are well-developed societies. Hence, Liberia can emulate these nations in its national reconstruction and socioeconomic development by providing free and compulsory education from kindergarten through high school or two-year community or technical college.

In essence, prioritizing education, health, and infrastructure development” is the best way forward for Liberia in its national reconstruction and economic stabilization drives. For I believe that while the lack of job and housing opportunities may seem on the surface as the most pressing demands in Liberia today, the reality is that without health and education, the chances of many Liberians occupying new homes and taking over new jobs in the near future are slim. I believe that if in this age of information technology and economic globalization the Liberian educational system is not revamped to train Liberians in the relevant marketable skills that will enable Liberians to compete amongst themselves in Liberia and with people on the international market, then the country will be doomed to failure. Conversely, I believe that if the national healthcare system in the new Liberia is not improved to give Liberians easy access to modern healthcare services and delivery systems, then Liberians may not be healthy enough to attend school and undertake other meaningful tasks necessary for socioeconomic growth and development in the new Liberia. And this is why I strongly believe that now or in the future the only two essential ingredients that I see for stimulating national unity, peace, reconciliation, and socioeconomic growth and development in the new Liberia are health and education. Hence, I am pleased to share with you my vision for the promotion of health and education in Liberia under the topic, “Health & Education Imperatives for the New Liberia: A Proposal for Collective Action.”

Ladies and gentlemen, education is generally the bedrock, the lifeline, or the wealth of any nation. But education cannot be the bedrock or lifeline of a nation unless education is structured to develop the productive capacities of people of the local culture or society. In other words, education must be able to train the citizens or students of a country not only to be statesmen and stateswomen, but also to honorably use the knowledge acquired at school for the attainment of power, selflessness, brotherhood, community involvement, nationalism, spirituality, and global awareness. And this means that the education offered in Liberia must be relevant to the development of goals and aspirations of Liberia by insisting on Liberian cultural values, norms, and mores. Education must be the local fountain of knowledge, as many educational scholars and psychologists have argued consistently that one of the things that separates human brings from animals is knowledge. Hence, knowledge is the oxidizer for the development, growth, and evolution of human beings worldwide. Yet the acquisition of knowledge mostly takes place through a national educational system backed by a curriculum designed to enable the learners to adequately cultivate their gifts and talents via the attainment of knowledge.

Consequently, education as a facilitator of individual knowledge and skill seeks to instill patriotism and nationalism in society, by removing all forms of hatred, racism, tribalism, sectionalism, fear, disease, poverty, and self-destruction associated with a lack of education or knowledge. And this is why many great nations of the world continued to invest heavily in education to serve as a social bond for national unity and development. Unfortunately, the education system in Liberia has played down Liberian cultural values and emphasized foreign values and ideologies so much so that many graduates of the Liberian school system are more familiar with French, German, English, American, and other Eurocentric studies and cultural values than Liberian and African studies and cultural values. As a result, many Liberians alive today are generally clueless about what it means to be a Liberian, as they tend to harbor no sense of patriotism and nationalism as Liberians. Most Liberians have no commitment or imagination regarding the present and future of Liberia because the Liberian educational system has failed to educate Liberians about the “burdens of Liberian statehood and the responsibilities of Liberian citizenship,” as one of LIHEDE’s co-founders, Mr. Nat Gbessagee described in a recent article. The educational system in Liberia must, therefore, be restructured to teach Liberian cultural values and skills that are relevant to the reconstruction of Liberia.

The new educational system of Liberia must recognize and emphasize knowledge, skills, attitudes, Liberian cultural values and norms that are directly codified into the national curriculum of Liberia to prepare Liberian citizens for the task of nation building for present and future generations of Liberians, as opposed to the current heavy reliance on foreign expertise for operating the education systems in Liberia. The content of the new educational system and national curriculum in Liberia must emphasize Liberian language, geography, history, mathematics, science, physical sciences, religion, and other tasks for national survival as a nation and people. In essence, the new educational system and national curriculum in Liberia must embody the Liberian way of life in terms of the national survival, identity, knowledge, attitudes, skills, values, customs, traditions, norms, beliefs, practices, technology, and cultural artifacts. I believe that if Liberian cultural values and the requisite skills for national development are codified into the national curriculum and taught in Liberian schools, Liberians will prosper as a nation and people both in terms of peace, national unity, and development. Indeed, the Liberian educational system has over the years failed the Liberian nation and people by creating a group of Liberian citizens who have yet to know what they must learn today in order to create the Liberia of tomorrow. But I believe this shortcoming in the Liberian educational system is bound to change with a restructured educational system and national curriculum that emphasize Liberian cultural values and manpower needs, since no nation can truly develop and prosper without clear national values, identities, and development aspirations or goals.

Fellow Liberians and friends of Liberia, the education we offer in Liberia cannot by itself be relevant to the growth and development of Liberia unless it is structured in a way that caters to the manpower needs and cultural values of Liberia. But sadly, in the last 160 years our national independence, the educational system in Liberia has been so detached from the manpower training needs and cultural values of Liberia that many Liberians graduated from high school and college without the relevant technical knowledge, marketable skills, and cherished sense of local Liberian values and belongingness, which are key stimulants for socioeconomic and development growth in any country. As a result of this poorly structured educational system, many Liberian citizens are not technically, professionally, and culturally savvy to take on the responsibility of nation building, so outside help is often sought in every aspect of Liberian development objectives. This trend of educational development in Liberia must be stopped and changed for good if Liberians are to become productive citizens in Liberia. Hence, the educational system in Liberia must be revised or restructured to prepare Liberians for leadership roles in Liberian society, with a national curriculum that emphasizes Liberian cultural values, identity, patriotism, and nationalism.

The Liberian educational system, in essence, must begin to produce Liberian scholars and professionals who value and love Liberia above all other foreign entities and systems, and who are willing and ready to conform to Liberian national standards, expectations, and development goals and aspirations. But Liberia cannot restructure its educational system and national curriculum in the absence of tapping into the broad perspectives of the Liberian people. For I believe that any workable solutions to the problems facing the new Liberia in the education and health sectors of the national economy demand the kind of insights that are likely to emerge from the diverse perspectives, experience, and ingenuity to be gained from this forum. And this is why I want to acknowledge the many wonderful ideas I have heard so far from the array of distinguished speakers during the past several hours. It is my hope that the Symposium Organizing Committee will synthesize these ideas into a comprehensive report to serve as a development guide for President Sirleaf and her government.

Now, please permit me to make a few disclosures about the Liberian History, Education, and Development, Inc. (LIHEDE), an organization I currently serve as executive director. At its very inception in 2003, LIHEDE set its eyes on promoting health and education in Liberia as a necessary first step to achieving historical accuracy and development in Liberia. LIHEDE identified two key projects in health and education, with malaria control, prevention, and eradication being its primary health project and a degree program in Liberian Studies at Liberian higher institutions of learning being its primary project in education. Consequently, LIHEDE drew up a curriculum in Liberian Studies for degree consideration at the bachelor’s, master’s, and PhD levels to educate Liberian students about the positive cultural values and norms of Liberia. Hence in 2004, after a series of consultations with the Liberian Minister of Education, the Liberian Head of State, and heads of Liberian colleges and universities, LIHEDE signed a memorandum of understanding each with the African Methodist University (AMU) and the African Methodist Episcopal University (AMEU) in Monrovia late 2004 to commence the first degree program in Liberian Studies by a Liberian higher institution of learning. And I am happy to report that as a result of the memorandum of understanding with AMEU, AMEU became the first higher institution of learning in Liberia to offer a first degree program in Liberian Studies beginning with the 2006 academic year. Indeed, the AMEU program in Liberian Studies is still slowing taking off, but the efforts is worth commendation for the inroad it has made so far to expose Liberian students to Liberian cultural values and mores in ways not previously possible at Liberian high schools and colleges.

At this juncture, though, the key question then becomes, “How should a program in Liberian Studies respond to current internal and external pressures to focus on national development in Liberia?” Well, one strategy would be to integrate Liberian Studies into the national curriculum of Liberia so that students from ABC (or Kindergarten) through college are exposed to the immediate cultural environments around them by learning the canons and other values of Liberian culture. And this is why a program in Liberian Studies at every grade level in Liberian schools will promote appreciation for the development of a national language in Liberia alongside English, which knowledge can go a long way in fostering unity, national security, development, and prosperity in Liberia. In essence, a program in Liberian Studies embedded in the national curriculum will clearly be one of the key mechanisms for training Liberian citizens of the present and future generations to appreciate Liberian cultural values, which by extension would mean knowing themselves and their obligations to the growth and development of Liberia as a matter of personal survival instead of relying on outsiders for basically everything as is the present case. ,

Ladies and gentlemen, the goal of education in general, and of any educational system in particular, is to develop the technical and managerial capacities of the local citizenry as a way for maintaining the political independence, socioeconomic growth and development, as well as the scientific or technological advancement of that nation, but this has not been the case in Liberia. For one of the drawbacks in the Liberian educational system is that by excluding Liberian cultural values in the national curriculum, Liberians deprived themselves of the knowledge of their origin and the diversity of their cultural identity. And this self-denial is a transgression beyond measurable proportion, which is tantamount to depriving oneself of the richness of one’s history, especially limiting the possibilities and solutions to national problems solving in Liberia. As a result of this self-denial of one’s cultural values, Liberians now operate like persons who go to fetch water at the well but with holes in the buckets while still expecting to fill the buckets with water. Hence, most of the problems we have encountered in Liberia, including the 14-year civil war, are a direct result of the lack of knowledge of our history, our culture, our identity, and our values as a nation and people. We now have the chance to restructure our educational system to meet these pressing challenges to national unity, development, and progress in Liberia.

Indeed, as Liberians discuss the essence of new educational system and a new national curriculum with a pure Liberian Studies component, all institutions of learning in Liberia, especially the nation’s highest institutions of learning must bear in mind that without a common framework binding all Liberians together, the Liberian society will not continue to exist in peace, and the nation will continue to disintegrate and be absorbed by other societies as the present case in post-conflict-Liberia, where outsiders are now calling the shots. Consequently, if Liberians hope to live together in peace as one people, then isn’t it time that they know something of the different cultures that make up this so-called Land of Liberty. My friends the sun must now rise in the new Liberia by being the true guidance of education and democracy for peace and development.

In fact, countries such as China, Japan, India, and the Four Asian Tigers nations are great political and economic powers in the world today not because they did not experience a regional war or civil war like Liberia, but rather because they provided an educational system and a national curriculum tied to their cultural values and manpower development goals. Liberia can do the same in restructuring its educational system to promote Liberian cultural values and manpower development goals not only like China, India, or Japan, but also like the fellow African states of Ghana, Nigeria, and Uganda, to new a few. In Nigeria, for example, the educational system is structured in such a way that hundreds of Nigerians today hold BA, MA, PhD degrees in local Nigerian culture and language studies, including the local languages of Ibo, Yoruba, Hausa studies, mainly from Nigeria’s Bayero University at Kano (www.kanoolie.com). In Uganda, the Ugandan Christian University (www.ugandastudies.org) does offer a degree program in Ugandan Studies.

As for Ghana, well, the educational system is structured in such a way that no student graduates from high school in Ghana without majoring and tutoring in one of the country’s national languages. And because the Ghanaian government invested heavily in this national linguistic pride since the early 1970s by training teachers to teach the various Ghanaian languages (GhLs)., Ghana is today one of the most popular destinations in all of Africa where many renowned foreign universities such as New York University, Temple University, Stanford University, University of Cambridge, University of Oxford, University of California, University of Guelph, University of Western Ontario, University of Leeds, University of Reading, University of Strathclyde, Pennsylvania State University, University of Ouagadougou, University of Copenhagen, University of Indiana, University of Bristol, University of West Florida, Free University of Brussels, University of Bergen, SUNY Brockport University of Ghana, Duke University, and the institution where I currently work, NC A&T State University, just to name a few, send their students regularly for summer immersion programs in African culture and history.

Liberia, the oldest independent republic in Africa, is not enjoying the same cultural respect as Ghana because the Liberian educational system failed to empower Liberians to learn about themselves through their culture and their language. Hence, the examples given of Ghana, Nigeria, and Uganda are convincing examples that speak to the fact that what is needed to propel the Liberian nation to the frontline is sound education reform—a new approach that does not leave any aspect of the nation’s history behind by embedding a Liberian Studies component in the national curriculum from elementary school through college. Liberian studies should also become one of the subject areas of the National Examination and no student should graduate from high school until he or she passes the Liberian Studies core exam.

We must make Liberian Studies the cornerstone of any educational reform and curriculum development activity in Liberia. We must bring education to the people wherever they are in order to easily promote an intellectual environment built on a commitment to free and open inquiry in the pursuit of freedom and truth. The educational system we promote must seek to inspire and encourage students to apply cultural and indigenous knowledge in their academic work and to present that knowledge within the parameters of intellectual discourse. Equally important, the national education in the new Liberia must provide wide ranging educational opportunities on and beyond our school campuses. The Liberian educational system must prepare traditional and non-traditional students, active professionals, and life-long learners to use the power of information media and technologies. This means that the new educational system must extend beyond the current emphasis on campus life or compulsory classroom attendance to distance learning opportunities in the 15 political subdivisions of Liberia at all grade levels, especially high school and college. Indeed, as an educator, I believe that all forms of education have worth irrespective of how, when, and where it is obtained. And as long as the students demonstrate their knowledge and skills in a way that reasonably conforms to those covered in specific high school, trade school, and college courses either by written or oral tests and examination, distance or location must not set the bounds for acquiring an education in the new Liberia. Effective learning, as every educator knows, is based on purposes and needs that are important to the individual and not necessarily where learning occurs, as different people learn in different ways, in accordance with their cultural and individual cognitive learning styles.

Even a College by Radio program presents a huge learning opportunity, as radio is a trusted source of information. Learning via radio does offer an opportunity for change, as Liberians can listen to radio in the privacy of their homes, in the village square, or farm house at break in a language with which they are comfortable. Of course, in addition to a college by radio program, other contents for non-degree students should be developed to rally and educate Liberians, especially the 80 percent who cannot currently read and write in English or another language. The new national educational system in the new Liberia must also engage, educate, and train community leaders to take ownership of the prevention and control of the deadly diseases in society. We as Liberians must look at what we have been doing wrong in our national educational system for educating our young people that is training them to go in a different direction than what we thought we were training them for. We must make a decision to do all we can to educate our citizens and young people in the ways of patriotism and nationalism in Liberia, something that seems lacking at the moment. It is a decision that requires a lot of sacrifices and some major changes in our national education philosophy. Our educational system need not require every Liberian to have a college degree, but rather it should emphasize that every Liberian must learn to read and write in both English and a Liberian language and must be able to learn one or two marketable skills that will make them productive citizens.

Apparently, we cannot achieve all of these goals under the old national curriculum which reduced Liberian cultural values and manpower development needs to nothingness. We need a new national curriculum and educational system in Liberia that will not only educate Liberians about Liberian cultural values, languages, and mores, but also train and produce more technicians and managers for national progress and development. Hence, while PhD and other advanced academic have their place in a post-conflict nation such as Liberia, but the development of Liberia will depend mostly on Liberian technicians and managers with at least a two-year technical degree. And this means that Liberia should begin to emphasize the acquisition of technical skills as opposed to only pure academic degrees in the local national curriculum. Liberia should also ask for foreign educational grants to train Liberian technicians for example in Norway in fishery; Japan, in auto mechanic; the United States, in manufacturing, and so forth. In other words, the Liberian Government should ask donor countries, donor agencies, development partners to collaborate with Liberian universities, especially in science and technology, polytechnics, junior colleges, technical or vocational institutions to build their institutional capacities and train the next group of Liberian professionals, managers, professors/teachers, technicians, etc. Liberia can do this in addition to sending students abroad for education or training.

Hence, I wish to make the following recommendations in support of a restructured Liberian educational system and national curriculum:

Education in the new Liberia should offer more technical courses or programs that are crucial for industrial development and economic growth in Liberia rather than continue to rely on liberal arts courses.

Education in the new Liberia should ensure that Liberia produces at least 25 Liberians in each professional or technical discipline in order for Liberians to take their rightful places in mining, manufacturing, and other professional and technical jobs in the country. To achieve these desired national goals, no more than a two-year degree should be required to afford many Liberians the opportunity to enter the technical professions as opposed to paying thousands of dollars to train one PhD student in political science. Such technical education should help develop the local manpower base of Liberia to man Liberian human and natural resources professionally.

Education in the new Liberia should be delivered under the appropriate conditions, if it is to gainfully contribute to economic growth. This means that education in the new Liberia should aim at providing universal primary education for all Liberians by 2025, with special attention given to adult education (GED) via radio, on-line or distance learning, and on-the- job training.

Education in the new Liberia should relate directly to the economic needs of Liberia, with greater weight being given to science and science applications that must have a Liberian Studies component to instill patriotism and nationalism. In other words, the Education in the new Liberia should place greater emphasis or priority on educating and ensuring that 85 of the Liberian population receives at least a secondary and post-secondary education in various technical disciplines required for economic development.

As part of promoting education in the new Liberia, the Liberian government should ask 50 nations to take in at least 10 Liberians for professional training in areas such as auto mechanic, air-conditioning, agriculture, aviation, woodwork, fishery, electrical engineering, computer engineering technology, road construction, building construction, nursing, radio engineering, wielding, manufacturing, surveying, small business development, restaurant and hotel management, environmental science, soil science, tourism, and graphic design, to name a few.

Now, ladies and gentlemen, let me focus on the second theme for my presentation, which is health. No one can argue that health is an essential component of every modern society, but, like education, if health services are unavailable or in short supply, the local population is bound to see great setbacks in personal health and national growth and development. Again, like the Liberian Studies program discussed earlier under the education theme, I like to point to current efforts by my organization, the Liberian History, Education, and Development, Inc. (LIHEDE) to create public awareness about the dangers of malaria to the socioeconomic growth and development of Liberia. Hence, I cannot talk about the role of healthy people in the reconstruction of Liberia without first referencing efforts by LIHEDE.

I returned from Liberia in mid August this year after a two-week visit to Liberia that included the launching of a LIHEDE’s culture-driven malaria program in Buchanan, Grand Bassa County, a program which seeks to channel malaria prevention and control efforts through the use of local cultural institutions, traditional Liberian languages, and sports, especially football or soccer. This recent trip to Liberia was my tenth in the last couple of years on LIHEDE business. In fact, for the past three years, LIHEDE has effortlessly held conferences in the United States and Liberia, including the 2005 symposium on “combating malaria in post-conflict Liberia,” and the historic 2006 National Health Conference held in Liberia in December 2006 in collaboration with the Liberian Ministry of Health and Social Welfare and other public and private agencies, aimed at bringing to the consciousness of the Liberian people and the world the magnitude of the impact of malaria in Liberia. And one of the highlights of the 2006 Conference was an invitation extended to officials of LIHEDE by the US Embassy in Monrovia to witness the historic announcement made by President George W. Bush via satellite, naming Liberia as a focused country to benefit from the President Malaria Initiative (PMI) funds. LIHEDE had written several letters to U.S. authorities after the 2006 malaria symposium in the U.S. to include Liberia on the President Malaria Initiative (PMI), so the U.S. Embassy’s invitation to LIHEDE officials was not a surprise. However, LIHEDE is glad that as a focused nation of PMI, Liberia is expected to receive 2.5 million US dollars in 2007 and 12 million US dollars in 2008 to combat malaria in Liberia.

Generally, though, LIHEDE is pleased but not yet satisfied with current gains in its malaria prevention and control drive until malaria is completely eradicated on Liberian soil. Hence, we in LIHEDE are developing an active civic society (Liberians and Friends of Liberia) in the Diaspora to come up with plans and programs to assist in the implementation of the 2006 National Malaria Conference Resolution in order to ensure that benefits from the PMI directly impact the vast majority of the population of Liberia who live in rural communities. But malaria is not the only health issues in Liberia today. Liberia is saddled with a lot of health issues associated with poor sanitation, unsafe drinking water, housing congestions, environmental health and safety issues, and problems of high incidence of tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS, as TB, HIV/AIDS, and malaria the three main killer diseases in Liberia and most of the Third World today.

The World Health Organization lists Liberia as one of two nations with the highest rate of malaria in the world, noting that about 90% of the population of Liberia is exposed to malaria on a continuous basis. In fact, in the Liberian capital, Monrovia, where majority of the educated population and key national decision-markers are concentrated, more than 50% of all hospitals and clinics’ visits by patients are said to malaria-related, while, according to the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Liberia, there are about only four functioning hospitals in Liberia with an estimated 237 physicians/specialists or 0.1 physicians per 100,000 patients. In addition, more than one of every five newborn Liberian children will not live to celebrate their 5th birth day due to malaria, while Liberia currently leads the world in highest newborn crude death rate at 66 deaths per 1,000 births. Indeed, with these kinds of statistics which continued to put much burden on the inadequate resources of both the government and the people of Liberia, it is now time to act and act now to prevent malaria in Liberia to help to lay the foundations for a better nation after the battle against malaria has been won.

Moreover, Liberian government health records indicate malaria not only claims 65,000 lives each year, but that the government also spends in excess of US$40 million each year to combat malaria. This huge amount does not even include what poor malaria-stricken Liberian families spend, which is often up to 35% of their income on malaria prevention and treatment, excluding amounts for burial from malaria deaths. But more troubling is that Liberian families continue to live on meager 30 cent per day per person as noted recently by former World Bank President Paul Wolfowitz, even as these families continue to spend in excess of 35% of their income on malaria treatment and prevention. But the health situation in Liberia today is not unique to Liberia. As far back the late 1200 BC, the Egyptian Monarch or Pharaoh Ramses II (1290 to 1224 B.C.), popularly known as the great builder-king, established industrial medical services to safeguard a huge slave workforce and the employee/architectural staff. By Ramses’ command, architects and certain other employees working on huge Egyptian pyramids and other national projects were required to decontaminate themselves daily by bathing in the Nile River. Regular staff and slave workers were each also required to pass daily medical examinations so that they, in turn, would not contaminate Ramses' temples. During that time, when doctors found a worker with communicable disease, that worker was quarantined to preclude any chances of the disease spreading among the workforce and bringing the work to a standstill.

Indeed, Ramses knew first hand that a sick workforce could not build great nation, especially huge pyramids in the absence of machines, so the workers had to submit to daily decontamination exercises and quarantine to safeguard the health of everyone. Unlike the times of ancient Egypt, many health standards and remedies now exist to combat any number of diseases in the world. But like Ramses’ Egypt, Liberia needs her sons and daughters to take steps to combat malaria, HIV/AIDS and other communicable diseases in Liberia in order to keep the Liberian people healthy at all times to help in the national rebuilding process. The challenge is, however, great because right now, according to recent report, HIV/AIDS victimizes 400,000 Liberians, 600,000 tested positives. The report went on to say that over 12 percents of the nation’s estimated 3.5million are in trouble. And the trend is even worrisome in that it is predicted by Liberian and international health professionals that one in every 4 to 6 Liberian children would lose a parent to HIV/AIDS in 2010. Hence, Liberia, a nation with less than four million people, is at serious risk from the combined forces of malaria, HIV/AIDS and low life expectancy of 41 years for males and 47 years for females.

Consequently, establishing quality health systems throughout Liberia should be a national priority in the new Liberia, with emphasis on the construction of more modern health centers, clinics, and hospitals, and the training of health workers at every professional grade level. Hence, the alleviate or reduce poverty and inequality in health services access and distribution in Liberia, and to lay the foundation for sustained economic, political, and cultural growth in Liberia, investment in health education and training should be the primary preoccupation of every Liberian or friend of Liberia in order to create a nation of mostly healthy people. And it is in this context that I make the following recommendations for the improvement in the health delivery systems of Liberia:

Health education in the new Liberia should enable our people to read, reason, communicate and make informed choices treatment options for malaria and other common diseases in Liberia. This means that health education in the new Liberia should include individual and community mobilization for malaria control via an ongoing community radio campaign, with massive education components delivered in Liberian languages in creating public awareness about malaria and such other diseases.

Health education in the new the Liberia should seek to increase individual productivity and quality of life, since only healthy people can build the new democratic Liberia. This can be done by including health education in the national curriculum of Liberian schools, so that children and parents can become more familiar with malaria, HIV/AIDS, TB, and other diseases, what causes them, how to recognize their symptoms, how to prevent and treat the diseases, and how to reduce health hazards and other pollutants in Liberian neighborhoods and communities.

Health and safety activities in the new Liberia should including the building of more health facilities and the training of at least 5,000 national emergency responders (midwives and physician assistants) in a sustainable train-the trainers program to combat malaria and other common diseases in Liberia.

Health and safety activities in the new Liberia should solicit and include the full participation of rural community leader and women’s health groups at the town, village, and district levels. Such efforts should utilize traditional Liberian council of elders, herbal remedies, and other collaborative efforts and actions necessary to create a healthy Liberian nation and people.

Health and safety activities in the new Liberia should also include school hour screening for malaria

At some point in this presentation, I indicated that my organization, LIHEDE, launched its “culture-driven” malaria program in Buchanan, Grand Bassa County by appealing to the people to use of traditional cultural methods available to them in each local community to join the fight against malaria prevention and control in Liberia. Generally, the goal of a culture-driven malaria initiative of the kind launched by LIHEDE is to empower the people to undertake malaria education projects in Liberia that encompass teaching about malaria in Liberian schools, using radio scripts in Liberian vernacular languages to educate and rally the support of Liberians outside the city centers in combating malaria and establishing malaria free zones across Liberia in the campaign for malaria control, prevention, and eradication in Liberia. It is also contemplated that annual soccer tournaments will be held in Liberia to promote malaria awareness in Liberia as a model for the rest of Africa, since soccer is a very popular sport in Liberia and Africa in general.

Indeed, throughout my presentation on the on health and education, I see a common thread or reality that binds the two together. And that the reality is that without a healthy people, there can be no education because the two supplement each other in terms of function or importance of health and education in the drive toward peace, unity, national reconstruction, and development in Liberia. In essence, we must in the new Liberia spread education like rice seeds in all every sector of the national economy. By spreading our human capacity in all sphere of education and health development in Liberia, we will be educating ourselves about our survival as a national and people in developing and protecting our democracy. For without educating ourselves about our health and development needs, we are doomed to failure as a people, and our democracy will perish for lack of active participation of our citizens. Hence, the unprecedented challenges of the new Liberia will not be resolved unless we realize that our present and future problems cannot be solved without the involvement of our people through education.

I believe we are ought to make a concerted effort to restructure or Liberianize the current national curriculum at all levels of the educational system in Liberia, if we desire to develop and promote an educated and healthy citizenry. I believe only by developing wiser systems of Liberian health and education, democratic systems of politics and governance, and social or civil systems of citizenship and activism, which creatively engage and educate all the Liberian people to the pressing challenges of the Liberian nation and people about their cultural values and environmental problems, will Liberians build for themselves a more desirable future that present and future generations of Liberians will be greatly proud of. Thus, in the new Liberia, our students should learn about our own culture and traditions before they learn about the cultures of other countries, in order to develop a sense of belonging and identity that is seriously lacking in the present Liberia. In other words, until we the members of this present generation of Liberians create the capacity to believe in ourselves as to who we are, where we come from, where we are at the moment, and where we going, the next generation of Liberians will likely follow our footsteps.

This is why it is very important for the educational system and national curriculum in Liberia to be restructured or revamped to force Liberians to pay special attention to their motherland by learning about Liberian cultural values, norms, mores, taboos, and traditions as well as how to coexist and relate one another as patriotic citizens. Indeed, today, we as Liberians have lost sense of our identity and our roots because we failed to teach our cultural values and traditions to ourselves and to our children. But we cannot allow ourselves to be blown like a big balloon by the wind, without any sense of direction. I believe we will have vision and mission by choosing what is good from our cultures and reject what is bad. I believe if we learn to come together and work together as one group of people with the same destiny, we will learn collectively how to identify and preserve what is good about our own cultures and discard what is bad about our culture. But we can never achieve unity and cultural cohesion in Liberia unless we Liberianize the health and educational systems in Liberia to solidify our unity and our development as a nation and people. I think you.

----------------------------------------------------------

Syrulwa Somah, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor of Environmental Health and Occupational Safety and Health at NC A&T State University in Greensboro, North Carolina. He is author of several books, including, The Historical Resettlement of Liberia and Its Environmental Impact; Christianity, Colonization and State of African Spirituality, and Nyanyan Gohn-Manan: History, Migration & Government of the Bassa (a book about traditional Bassa leadership and cultural norms published in 2003). Somah is also the Executive Director of the Liberian History, Education & Development, Inc. (LIHEDE), a nonprofit organization based in Greensboro, North Carolina. He can be reached at: somah@ncat.edu This e-mail address is being protected from spam bots, you need JavaScript enabled to view it

; lihede2003@yahoo.com This e-mail address is being protected from spam bots, you need JavaScript enabled to view it

|